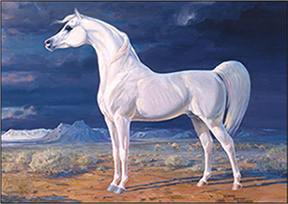

The purebred Arabian horse is striking. An Arabian's most identifiable characteristics are its finely chiseled head, dished face, long arching neck and high tail carriage. Its entire appearance exudes energy, intelligence, courage and nobility. Every time an Arabian moves in its famous "floating trot," he announces to the world his proud, graceful nature.

In general, Arabians have a short, straight back (usually one less vertebra than is common with other breeds), perfect balance and symmetry, a deep chest, well-sprung ribs, strong legs of thick density and a more horizontal pelvic bone position.

Five key elements distinguish type

(descriptions in italics are quoted from the Breed Standards found in the Arabian Chapter of the USEF Rule Book):

Head - Comparatively small head, profile of head straight or preferably slightly concave below the eyes; small muzzle, large nostrils, extended when in action; large, round, expressive, dark eyes set well apart (glass eyes shall be penalized in Breeding classes); comparatively short distance between eye and muzzle; deep jowls, wide between the branches; small ears (smaller in stallions than mares), thin and well shaped, tips curved slightly inward

Neck - long arched neck, set on high and running well back into moderately high withers

Back - short back

Croup - croup comparatively horizontal

Tail - natural high tail carriage. Viewed from rear, tail should be carried straight

The above qualities identify type in the purebred Arabian horse. If the horse has these qualities and correct conformation, we have our ideal standard.

Click here to learn more about different body parts and what makes the Arabian horse unique.

Unparalleled beauty, a rich history and a unique ability to bond with their owners.

For thousands of years, Arabians lived among the desert tribes of the Arabian Peninsula, bred by the Bedouins as war mounts for long treks and quick forays into enemy camps. In these harsh desert conditions evolved the Arabian with its large lung capacity and incredible endurance.

Historical figures like Genghis Khan, Napoleon, Alexander The Great and George Washington rode Arabians. Even today, one finds descendants of the earliest Arabian horses of antiquity. Then, a man's wealth was measured in his holdings of these fine animals. Given that the Arabian was the original source of quality and speed and remains foremost in the fields of endurance and soundness, he still either directly or indirectly contributed to the formation of virtually all the modern breeds of horses.

The prophet Mohammed, in the seventh century A.D., was instrumental in spreading the Arabian's influence around the world. He instructed his followers to look after Arabians and treat them with kindness. He said that special attentions should be paid to the mares because they insure the continuity of the breed. He also proclaimed that Allah had created the Arabian, and that those who treated the horse well would be rewarded in the afterlife.

The severe climate required the nomads to share food and water, and sometimes even their tents with their horses. As a result, Arabians developed a close affinity to man and a high intelligence.

Over the centuries, the Bedouin tribes zealously maintained the purity of the breed. Because of their limited resources, breeding practices were extremely selective. Such practices, which eventually helped the Arabian become a prized possession throughout the world, have led to the beautiful athletic breed we know today, which is marked by a distinctive dished profile; large, lustrous, wide-set eyes on a broad forehead; small, curved ears; and large, efficient nostrils.

Even today the purebred Arabian is virtually the same as that ridden in ancient Arabia. Arabians now display their athletic talents in a variety of disciplines from English to Western, with the Arabian positioned as the undisputed champion of endurance events.

If you're looking for a companion who'll be your partner in adventure or competition - and your friend for life - then an Arabian may be the horse for you.

When we first encounter the Arabian, or the prototype of what is known today as the Arabian, he is somewhat smaller than his counterpart today. Otherwise he has essentially remained unchanged throughout the centuries.

Authorities are at odds about where the Arabian horse originated. The subject is hazardous, for archaeologists' spades and shifting sands of time are constantly unsettling previously established thinking. There are certain arguments for the ancestral Arabian having been a wild horse in northern Syria, southern Turkey and possibly the piedmont regions to the east as well. The area along the northern edge of the Fertile Crescent comprising part of Iraq and running along the Euphrates and west across Sinai and along the coast to Egypt, offered a mild climate and enough rain to provide an ideal environment for horses. Other historians suggest this unique breed originated in the southwestern part of Arabia, offering supporting evidence that the three great riverbeds in this area provided natural wild pastures and were the centers in which Arabian horses appeared as undomesticated creatures to the early inhabitants of southwestern Arabia.

Because the interior of the Arabian Peninsula has been dry for approximately 10,000 years, it would have been difficult, if not impossible, for horses to exist in that arid land without the aid of man. The domestication of the camel in about 3,500 B.C. provided the Bedouins (nomadic inhabitants of the Middle East desert regions) with means of transport and sustenance needed to survive the perils of life in central Arabia, an area into which they ventured about 2,500 B.C. At that time they took with them the prototype of the modern Arabian horse.

There can be little dispute, however, that the Arabian horse has proved to be, throughout recorded history, an original breed, which remains to this very day.

History does not tell us where the horse was first domesticated, or whether he was first used for work or riding. He probably was used for both purposes in very early times and in various parts of the world. We know that by 1,500 B.C. the people of the East had obtained great mastery over their hot-blooded horses, which were the forerunners of the breed that eventually became known as "Arabian."

About 3,500 years ago the hot-blooded horse assumed the role of kingmaker in the East, including the Valley of the Nile and beyond, changing human history and the face of the world. Through him the Egyptians were made aware of the vast world beyond their own borders. The Pharaohs were able to extend the Egyptian empire by harnessing the horse to their chariots and relying on his power and courage. With his help, societies of such distant lands as the Indus Valley civilizations were united with Mesopotamian cultures. The empires of the Hurrians, Hittites, Kassites, Assyrians, Babylonians, Persians and others rose and fell under his thundering hooves. His strength made possible the initial concepts of a cooperative universal society, such as the Roman Empire. The Arabian "pony express" shrank space, accelerated communications and linked empires together throughout the eastern world.

This awe-inspiring horse of the East appears on seal rings, stone pillars and various monuments with regularity after the 16th century B.C. Egyptian hieroglyphics proclaim his value; Old Testament writings are filled with references to his might and strength. Other writings talk of the creation of the Arabian, "thou shallst fly without wings and conquer without swords." King Solomon some 900 years B.C. eulogized the beauty of "a company of horses in Pharaoh's chariots," while in 490 B.C. the famous Greek horseman, Xinophon proclaimed: "A noble animal which exhibits itself in all its beauty is something so lovely and wonderful that it fascinates young and old alike." But whence came the "Arabian horse?" We have seen this same horse for many centuries before the word "Arab" was ever used or implied as a race of people or species of horse.

The origin of the word "Arab" is still obscure. A popular concept links the word with nomadism, connecting it with the Hebrew "Arabha," dark land or steppe land, also with the Hebrew "Erebh," mixed and hence organized as opposed to organized and ordered life of the sedentary communities, or with the root "Abhar"-to move or pass. "Arab" is a Semitic word meaning "desert" or the inhabitant thereof, with no reference to nationality. In the Koran a'rab is used for Bedouins (nomadic desert dwellers) and the first certain instance of its Biblical use as a proper name occurs in Jer. 25:24: "Kings of Arabia," Jeremiah having lived between 626 and 586 B.C. The Arabs themselves seem to have used the word at an early date to distinguish the Bedouin from the Arabic-speaking town dwellers.

This hot-blooded horse, which had flourished under the Semitic people of the East, now reached its zenith of fame as the horse of the "Arabas." The Bedouin horse breeders were fanatic about keeping the blood of their desert steeds absolutely pure, and through line breeding and inbreeding, celebrated strains evolved which were particularly prized for distinguishing characteristics and qualities. The mare evolved as the Bedouin's most treasured possession. The harsh desert environment ensured that only the strongest and keenest horse survived, and it was responsible for many of the physical characteristics distinguishing the breed to this day.

Additional Resource: W.K. Kellogg Arabian Horse Library from Cal Poly Pomona

"An Arabian will take care of its owner as no other horse will, for it has not only been raised to physical perfection, but has been instilled with a spirit of loyalty unparalleled by that of any other breed."

Somewhere in the inhospitable deserts of the Middle East centuries ago, a breed of horse came into being that would influence the equine world beyond all imagination. In the sweet grass oasis along the Euphrates and Tigris Rivers in the countries that are now known as Syria, Iraq and Iran, and in other parts of the Arabia peninsula, this hearty horse developed and would soon be known as the Arabian horse.

To the Islamic people, he was considered a gift from Allah, to be revered, cherished and almost worshipped. Long before Europeans were to become aware of his existence, the horse of the desert had established himself as a necessity for survival of the Bedouin people. The headmen of the tribes could relate the verbal histories of each family of horse in his tribe as well as he could each family of Bedouin. The mythology and romance of the breed grew with each passing century as stories of courage, endurance and wealth intermingled with the genealogies.

The very nature of the breed, its shape as well as its color, was influenced by religious belief, superstition and tradition. It was believed that the bulging forehead held the blessings of Allah. Therefore the greater the "Jibbah" the greater the blessings carried by the horse. The great arching neck with a high crest, the "Mitbah" was a sign of courage, while a gaily-carried tail showed pride. These traits were held in high esteem and selectively bred for.

Due in part to the religious significance attached to the Arabian horse, as well as the contribution it made to the wealth and security of the tribe, the breed flourished in near isolation. Traditions of breeding and purity were established to keep the breed "Asil" or pure, in the form intended by Allah. Any mixture of foreign blood from the mountains or the cities surrounding the desert was strictly forbidden. While other, desert type breeds developed in North Africa and the periphery of the Great Desert, they were definitely not of the same blood as Arabians and were disdained by the proud Bedouin.

The Arabian horse was primarily an instrument of war, as were horses in general in most societies of the time. A well-mounted Bedouin could attack an enemy tribe and capture their herds of sheep, camels and goats, adding to the wealth of their own tribe. Such a raid was only successful if the aggressors could attack with surprise and speed and make good their escape. Mares were the best mounts for raiding parties, as they would not nicker to the enemy tribe's horses, warning of their approach. The best war mares exhibited great courage in battle, taking the charges and the spear thrusts without giving ground. Speed and endurance were essential as well, for the raids were often carried out far from the home camp, family and children.

The Bedouin people could be as hospitable as they were war like. If a desert traveler touched their tent pole, they were obligated to provide for this "guest", his entourage and animals for up to three days without request for payment. A welcome guest would find his mare's bridle hung from the center pole of his hosts' tent to indicate his status. In this way, tribes that were often at war would meet and, with great hospitality, break bread and share stories of their bravest and fastest horses.

Races were held with the winner taking the best of the losers herd as their prize. Breeding stock could be bought and sold, but as a rule, the war mares carried no price. If indeed they changed hands it would be as a most honored gift. Through the centuries the tribes who roamed the northern desert in what is now Syria became the most esteemed breeders of fine horses. No greater gift could be given than an Arabian mare.

The value placed upon the mare led inevitably to the tracing of any family of the Arabian horse through his dam. The only requirement of the sire was that he be "Asil". If his dam was a "celebrated" mare of a great mare family, so much the better. Mare families, or strains, were named, often according to the tribe or sheik who bred them.

The Bedouin valued pure in strain horses above all others, and many tribes owned only one main strain of horse. The five basic families of the breed, known as "Al Khamsa", include Kehilan, Seglawi, Abeyan, Hamdani and Hadban. Other, less "choice" strains include Maneghi, Jilfan, Shuwayman, and Dahman. Substrains developed in each main strain, named after a celebrated mare or sheik that formed a substantial branch within the main strain.

A great story of courage, endurance, or speed always accompanied there citation of the genealogy of the sub-strain, such as the great Kehilet al Krush, the Kehilet Jellabiyat and the Seglawi of Ibn Jedran. Each of these mares carried with them stories of great battles and intrigue. Their daughters were sought after by the most powerful kings but often remained unattainable. Daughters and granddaughters of these fabled mares changed hands through theft, bribery and deceit. If any of their descendants were sold, the prices were legendary.

Each strain, when bred pure, developed characteristics that could be recognized and identified. The Kehilan strain was noted for depth of chest, masculine power and size. The average pure in strain Kehilan stood up to 15 hands. Their heads were short with broad foreheads and great width in the jowls. Most common colors were gray and chestnut.

The Seglawi was known for refinement and almost feminine elegance. This strain was more likely to be fast rather than have great endurance. Seglawi horses have fine bone, longer faces and necks than the Kehilan. The average height for a Seglawi would be 14.2 hands, the most common color Bay.

The Abeyan strain is very similar to the Seglawi. They tended to be refined. The pure in strain Abeyan would often have a longer back than a typical Arabian. They were small horses, seldom above 14.2 hands, commonly gray and carried more white markings than other strains.

Hamdani horses were often considered plain, with an athletic if somewhat masculine, large boned build. Their heads were more often straight in profile, lacking an extreme Jibbah. The Hamdani strain was one of the largest, standing as much as 15.2 hands. The common colors were gray and bay.

The Hadban strain was a smaller version of the Hamdani. Sharing several traits including big bone and muscular build. They were also known for possessing an extremely gentle nature. The average height of a Hadban was 14.3 hands, the primary color brown or bay with few if any white markings.

While the Bedoiun bred their horses in great obscurity, the highly war like people of the East rode their Barbs and Turks into Europe, bringing havoc with them and leaving waste in their wake. Though few Arabian horses accompanied the Turks and Vandals on their forays into Europe, their hardy Barb and Turkish mountain horses were no less impressive to their victims.

Europe had developed horses through the Dark Ages to carry a knight and his armor. Their lighter horses were from the pony breeds. They had nothing to compare with the small, fast horses upon which the invaders were mounted. An interest in these "Eastern" horses grew, along with fantastical stories of prowess, speed, endurance and even jumping ability. To own such a horse would not only allow for the improvement of local stock, but would endow the fortunate man with incredible prestige. Such a horse in the stable would rival the value of the greatest artwork hung on the wall. Europeans of means, primarily royalty, went to great lengths to acquire these fabled horses.

As the world slowly shrank due to increasing travel abroad, the Turkish rulers of the Ottoman Empire began to send gifts of Arabian horses to European heads of state. Such was the nature of The Godolphin Arabian (sometimes called "Barb") imported to England in 1730 as well as The Byerley Turk (1683) and the Darley Arabian (1703). These three "Eastern" stallions formed the foundation upon which a new breed, the Thoroughbred, was to be built. Today 93% of all modern Thoroughbreds can be traced to these three sires. By direct infusion, and through the blood of the Thoroughbred, the Arabian has contributed, to some degree to all our light breeds of horses.

The Arabian horse also made inroads into other parts of Europe and even farther East. In France, the Arabian helped to make the famous Percheron. In Russia, the blood of the Arabian horse contributed to the development of the Orloff Trotter.

The Bedouins have generally been credited with the beginning of selective pure breeding of Arabian horses. These tribes, although their breeding records were kept by memory and passed down through the ages verbally, are also credited as the first to keep breeding records and maintaining the purity of the Arabian breed. To this date, many Arabian pedigrees can be traced to desert breeding meaning there is no written record but because of the importance of purity to the Bedouins, "desert bred" is accepted as an authentic verification of pure blood for those early imports.

Today the Arabian horse exists in far greater numbers outside of its land of origin than it ever did in the Great Desert. In the early part of the last century; greed, ambition, desire for prestige, as well as an honest interest in saving the breed from extinction was the driving force behind governments, royal families and adventuring private citizens alike in the acquisition and propagation of this great prize of the Bedouin people--the Arabian horse.

European horses soon felt an extensive infusion of Arabian blood, especially as a result of the Christian Crusaders returning from the East between the years 1099 A.D. and 1249 A.D. With the invention of firearms, the heavily armored knight lost his importance and during the 16th century handy, light and speedy horses were in demand for use as cavalry mounts. Subsequent wars proved the superiority of the Arabian horse as the outstanding military mount throughout the world.

After the Crusades, people of the Western world began looking to the people of the East for Arabian bloodstock. Between 1683 and 1730 a revolution in horse breeding occurred when three Arabian stallions were imported to England. The Darley Arabian, the Byerly Turk and the Godolphin Arabian founded the Thoroughbred breed. Today the majority of all modern Thoroughbreds can be trace to these three Arabian sires. By direct infusion, and through the blood of the Thoroughbred, the Arabian has contributed, to some degree, to all our light breeds of horses.

After the Crusades, people of the Western world began looking to the people of the East for Arabian bloodstock. Between 1683 and 1730 a revolution in horse breeding occurred when three Arabian stallions were imported to England. The Darley Arabian, the Byerly Turk and the Godolphin Arabian founded the Thoroughbred breed. Today the majority of all modern Thoroughbreds can be trace to these three Arabian sires. By direct infusion, and through the blood of the Thoroughbred, the Arabian has contributed, to some degree, to all our light breeds of horses.

In the 1800's travelers in the Victorian era became enamored with the horse of the desert as significant Arabian stud farms were founded throughout Europe. The royal families of Poland established notable studs, as did the kings of Germany and other European nations. As a result of Lady Anne Blunt and Wilfred Blunt's historical sojourns into the desert to obtain Egyptian and desert stock, the world-famous Crabbet Arabian Stud was founded in England. This stud eventually provided foundation horses for many countries, including Russia, Poland, Australia, North and South America and Egypt.

In 1877, General Ulysses S. Grant visited Abdul Hamid II, His Imperial Majesty the Sultan of Turkey. There, he was presented with two stallions from the Sultan's stable, Leopard and Lindentree. Leopard was later given to Randolph Huntington who subsequently imported two mares and two stallions in 1888 from England. This program, limited as it was, must be considered as the first purebred Arabian breeding program in the U.S.

The Chicago Worlds Fair held in 1893 drew widespread public attention and had an important influence upon the Arabian horse in America. While every country in the world was invited to participate, Turkey chose to exhibit 45 Arabian horses in a "Wild Eastern" exhibition. Among the imported Arabians shown were the mare Nejdme and the stallion, Obeyran. Both subsequently became foundation animals No. 1 and No. 2 in the Arabian Stud Book of America (later changed to the Arabian Horse Registry of America and now, Arabian Horse Association). Several years later, two other mares and one stallion were also registered. Many breeding farms today have horses whose pedigrees trace to these 19th century Arabians.

Historical impor tations from England and Egypt were made soon after the Fair by such breeders as Spencer Borden, who imported 20 horses between 1898 and 1911 to his Interlachen Stud, and W.R. Brown who imported 20 horses from England, six from France and seven from Egypt between 1918 and 1932.

tations from England and Egypt were made soon after the Fair by such breeders as Spencer Borden, who imported 20 horses between 1898 and 1911 to his Interlachen Stud, and W.R. Brown who imported 20 horses from England, six from France and seven from Egypt between 1918 and 1932.

One of the most significant importations occurred in 1906 when Homer Davenport received permission from the Sultan of Turkey to export Arabian horses. Davenport, with the backing of then President Theodore Roosevelt, imported 27 horses that became the foundation of "Davenport Arabians." The Davenport importation of Arabian horses direct from the desert excited the few Arabian breeders in this country. This group of breeders decided that the time was right to form a registry to promote the horse and encourage the importation of new blood. In 1908, the Arabian Horse Club of America was formed (today known as the Arabian Horse Association) and the first studbook published. Recognition of the Arabian studbook by the U.S. Department of Agriculture established the Registry as a national registry and the only one for the purebred Arabian breed. Seventy-one purebred Arabians were registered at that point.

Another significant importation occurred in the 1920s, when the Kellogg Ranch, founded by W.K. Kellogg, brought in 17 select horses from the Crabbet stud farm in 1926 and 1927. Soon after, Roger Selby established the Selby Stud with 20 horses imported from Crabbet between 1928 and 1933. The Albert Harris importation consisted of two horses from England in 1924 and five from the Hejaz and Nejd desert regions in 1930 and 1931. Joseph Draper brought Spanish Arabians into the American picture when he imported five horses from Spain in 1934. J.M. Dickinson's Traveler's Rest Arabian Stud was established between 1934 to 1937 on an imported mare from Egypt and one from Brazil as well as seven mares from Poland. Henry B. Babson sent people to Egypt in 1932 who brought over two stallions and five mares. This farm still preserves the same bloodlines today.

In the 1940s and 1950s importations of Arabians to America slowed down as American breeding programs evolved from the previously imported stock. With the death of Lady Wentworth in 1957 and the dispersal of Crabbet Stud, importations in abundance were again made from England, and the post-war stud farms of Germany, Poland, Russia, Spain and Egypt were "rediscovered." Significant importations followed from these countries by several groups of dedicated breeders and again a new era of Arabian horse breeding dawned.

In 1919 W.R. Brown, then President of the Arabian Horse Registry, organized the first Cavalry Endurance Ride. The government had just established the U.S. Remount Service and there were only 362 registered Arabian horses in the country. It was a prime time to convince the government to breed Arabians. With so few Arabian horses, it was no easy task to find enough to adequately represent the breed in the endurance ride. However, the Arabs made a superior showing, taking most of the prizes including first. Mr. Brown won first place on his purebred Arabian mare RAMLA #347. RAMLA carried 200 pounds on the ride.

The second Cavalry Endurance Ride was held in 1920. The U.S. Remount Service, representing the Army, became much more involved in the ride this year. The Army wanted to increase the weight carried to 245 pounds and the Arabian owners agreed. The horses traveled sixty miles a day for five days with a minimum time of nine hours each day. The highest average points of any breed entered went to Arabians, although a grade Thoroughbred entered by the Army won first.

According to Albert Harris (Arabian Horse Registry Director 1924-1949), the (Thoroughbred) Jockey Club gave the Army $50,000 in 1921 to purchase the best Thoroughbreds they could find for that year's endurance ride. Mr. Harris wrote: "With two endurance rides to the credit of Arabian horses in 1919 and 1920, the U.S. Remount, and incidentally the Jockey Club, felt something had to be done to beat these little horses in the next ride..." The Army selected all Thoroughbreds or grade Thoroughbreds which were all ridden by Cavalry majors. The Army also wanted to lower the weight carried to 200 pounds, but the Arabian people, having proved their horses at 245 pounds, objected. A compromise was reached at 225 pounds.

In spite of the Army's efforts, the first prize in the 1921 Cavalry Endurance Ride went to W.R. Brown's purebred Arabian gelding *CRABBET #309. Mr. Brown won the trophy once again in 1923 with his Anglo-Arab gelding GOUYA.

Having won the race three times on his Arabians, Mr. Brown gained permanent possession of the U.S. Mounted Service Cup. Albert Harris wrote in his history of the Arabian Horse Registry that after 1923, the Arabian people decided not to enter their horses in the ride. This was done "so that the Army would have a chance of winning the cup the next time."

There was one exception. EL SABOK #276, an Arabian stallion owned by the U.S. Remount, finished first in 1925. He was not given the trophy because of a small welt raised under the cantle of his saddle. However, the U.S. Department of Animal Husbandry noted that of all stallions of various breeds entered in all of the rides, EL SABOK was the first and only one to finish a ride.

By this time the Army was convinced that Arabian horses had tremendous endurance ability and should be used to develop a supply of saddle horses that could be called to service if needed. Unfortunately, Arabians were scarce and difficult to obtain at that time. The Army breeding program was given a big boost in 1941 when the Arabian Horse Registry directors decided to donate the nucleus of an Arabian stud to the U.S. Remount. Each director and Mr. W.K. Kellogg (of the Kellogg cereal company) personally donated one or more horses. A total of one stallion, seven broodmares (six in foal), one suckling filly and three two-year-old fillies were placed at the Fort Robinson Remount Depot in Fort Robinson, Nebraska.

By 1943, the Army owned more Arabian horses than any other breed except Thoroughbreds. While Thoroughbreds were relatively easy to obtain because of the racing market, there were only 2,621 registered Arabians in the U.S. at that time!

That same year, Mr. W.K. Kellogg, a Registry Director from 1927 to 1940, and Albert Harris, helped the U.S. Remount Service to gain possession of Mr. Kellogg's Arabian stud in Pomona, California. Mr. Kellogg had originally given the stud to the state of California, but during World War II the Remount Service wanted it and they got it (including 97 purebred Arabians).

Only a few years later the Army decided to dispose of all its horse operations to the highest bidder. Mr. Kellogg, with much public support, arranged to have the ranch given to California Polytechnic College that continues to maintain an Arabian breeding program today.

Because the Arab often engaged in a form of desert warfare known as "Ghazu," a form of quick mounted foray upon his neighbors, his life and welfare depended upon the endurance and speed of his Arabian horse. These stellar qualities of the Arabian horse were also the natural result of a good original stock, which by intensive breeding in a favorable environment had maintained its purity. His blood is commanding to a remarkable degree, and invariably dominates all the breeds to which it is introduced and contributes its own superior qualities to them.

When imported to England, the Arabian became the progenitor of the Thoroughbred. In Russia, the blood of the Arabian horse contributed largely to the development of the Orloff Trotter. In France, the animal helped make the famous Percheron. And in America, again it was the Arabian horse that became the progenitor of the Morgan and through the English Thoroughbred, to make the Trotter.

As the oldest of all the light breeds and foundation stock of most, the Arabian is unique. The Arabian breed is different in that it does not exist as a result of selective breeding, as were other modern light breeds, where it was necessary to establish a registry prior to the development of the breed, but was a breed that had been recognized for thousands of years and had been maintained and cherished in its purity over those years as much as is humanly possible.

The high intelligence, trainability, gentle disposition and stamina of the Arabian enable it to excel at a wide variety of activities popular today. Arabians are excellent on the trail as well as in the show ring. Show classes in English and western pleasure, cutting and reining, even jumping and dressage provide opportunities for fun and enjoyment at both all-Arabian events and Open breed shows alike. As an endurance horse, the Arabian has no equal. The top prizes at endurance events almost always go to riders of Arabians. Arabian racing is another sport becoming more and more popular in recent years. In the past, considered the "Sport of Kings," Arabian racing is now enjoyed by racing enthusiasts at tracks across the country. In addition, the Arabians' Bedouin heritage is evident in their unequaled ability to bond with humans, making them the perfect horse for family members of all ages.

With today's prices comparable with other popular breeds, excellent Arabian horses are now accessible to a broad base of horse enthusiasts. And, with more living Arabian horses in the U.S. than in all the other countries in the world combined, America has some of the best horses and breeding farms from which to choose.

The traits that were bred into the Arabian through ancient times created a versatile horse that is not only a beautiful breed, but also one that excels at many activities. Considered the best breed for distances, the Arabian's superior endurance and stamina enable him to consistently win competitive trail and endurance rides.

The most popular activity with all horse owners is recreational riding-the Arabian horse is no exception. The loyal, willing nature of the Arabian breed suits itself as the perfect family horse. His affectionate personality also makes him a great horse for children.

In the show ring the Arabian is exceptional in English and western pleasure competition. The Arabian is well known for his balance and agility. Combined with his high intelligence and skillful footwork, he is more than capable in driving and reining events. For speed, agility and gracefulness, you'll want an Arabian. Arabians compete in more than 400 all-Arabian shows as well as in numerous Open shows around the U.S. and Canada.

The Arabian, as the original racehorse, is becoming more and more popular competing at racetracks throughout the country. Arabians race distances similar to Thoroughbreds, with more than 700 all-Arabian races held throughout the U.S. annually.

Although the most beautiful of all riding breeds, the Arabian is not just a pretty horse. He is an all-around family horse, show horse, competitive sport horse and work horse.

Purebred Arabian horses imported to England by Lady Ann Blunt became known as "Crabbet Arabians" after her farm, Crabbet Park. In the U.S., horses were associated with the individuals or farms that bred them, which explains why enthusiasts refer to "Babson," "Davenport" and "Kellogg" bloodlines. Egyptian Arabians are only those whose sires and dams descend from a special pool of horses used in the Egyptian purebred Arabian breeding program. Sometimes a horse bred in one country but acquired by another, either through sale or the spoils of war, is referred to by the nationality of its adopted country.The various bloodlines reflect the love and dedication that breeders have always had regarding the preservation, history and essence of this beautiful and captivating breed.

For additional information, contact marketing@arabianhorses.org